JIRA workflows for operations#

Note

This technote does not, at the present time, define Rubin Observatory policy or practice.

It proposes a process as a basis of further discussion.

Context#

Rubin has extensive and in some cases sophisticated workflows based on JIRA for anything from managing planned work, to reporting bugs, to defining validation campaigns, to managing staff travel. There are 12 highly active JIRA projects supporting this diverse collection of workflows and they are central to the working day of project staff.

With nightly telescope operations becoming a central focus, the question arises of how and to what extent to integrate night-time operations to the well developed workflows staff are already using. This document discusses some of the issues raised and proposes a workflow as a basis of further discussion.

Problem statement#

An over-simplified but still illustrative way to describe the nub of the debate on this issue is that for obvious and understandable reasons:

the observers, who primarily file tickets during the night, based on issues they encounter, would like to use a single workflow,

technical staff that perform work, based on issues encountered by the operators, would prefer to have those issues appear on the project their normal workflows are based on.

An example of the former is the JIRA OBS project and examples of the latter are the DM project used by the Data Management and Telescope & Site engineers for software work, the FRACAS project used by the Systems Engineering team for failure analysis work and the IT project

Solution spaces#

Unfortunately, there is no perfect solution when it comes to situations where people’s workflow preferences are in tension.

There are only three solution spaces to this kind of problem:

Do what is easiest for observers

Do what is easiest for technical staff

Create work and process to allow both to co-exist, e.g., by solutions such as people reassigning/re-filing/moving tickets from one project to the other.

Discussion

People tend to gravitate to option 3 for sociological reasons: it avoids upsetting whoever loses out on options 1 & 2, which are essentially incompatible. However, it’s not really a sustainable model as the default workflow: it places a burden on the person(s) doing the reconciliation, and it depends on this reconciliation being done every day including weekends, holidays, etc. It’s still a good safety net for making sure tickets are not miscategorized or forgotten, but it requires too much manual human intervention (or results in too much response latency) to be Plan A.

Option 2 may seem superficially the more sensible of 1 & 2 - there are more technical staff than night staff, and they have strongly rehearsed workflows before regular observing starts, and perhaps under some type of operations it might even make sense. However for ground-based astronomical observing there are some fairly severe problems with this model:

An observatory is a tightly integrated system, with hardware, software and environment all having to perform as a whole for observing to take place. It is very common that the initial bug report is due to a behavior of a system that is not the origin of the fault, for example data processing may raise an error that is due to the data being irreducable because the data suffers from a problem in the hardware or environment (as a very rare but real example, the data processing might raise an error about failing an astrometric fit that is actually due to the fact that there are no sources in the detector because the beam is vignetted by the dome). It is only after follow-up troubleshooting that the fault can be traced to the originating system.

Along those lines, there is not a 1:1 correspondence between the occurrence of a fault and a technical project to address it; for example a fault may result in both the software team needing to fix something, and the systems engineering team wanting to trace it to a verification failure

While every staff member’s time is valuable, observers are the staff whose immediate attention affects the most precious resource at a ground-based telescope, night-time observing time. Observers at night have large demands on their attention and are inundated by screens, dashboards, error messages and events requiring follow-up. If the process for them being able to file a ticket is not as lightweight as possible, the consequence tends to be that errors that should be attended to are not being captured.

Observatories (and one anticipates Rubin is no exception) use lost telescope time (clear night-time during which observing could have occurred but did not because of a fault) as a primary operational metric, and this metric is synthesized from a number of sources including declared lost time due to faults, which are the kind of metric that can be tracked in the OBS project.

The way an observer needs to interact with JIRA is not necessarily the same that an engineer wants to interact with JIRA: for example an observer wishes to note an event (or search for a past occurrence of an event) and is primarily interested in status (was the fault fixed) and response (what one should do in the event of an error) and not the kind of technical troubleshooting and approach discussion that is found in, say, DM tickets.

Filing faults that affect night-time observing in a dedicated project like OBS naturally surfaces them for urgent attention, and allows for special handling of new tickets, such as echoing them on slack channels. A slack channel that notifies of every new ticket filed in the OBS project is useful; one that echoes every new ticket in DM is certainly not; there are 40,000 tickets in the DM project before even the start of operations

Technical projects have their own specific requirements that are too onerous for a quick-capture project like OBS - everything from story points that are used for charging staff time to links with artifacts and requirements. They are very different from each other for good reasons, and this is why there are a dozen active projects in the first place.

An ideal workflow therefore has the following features:

Makes it as easy as possible for observers to capture faults in a ticket system and to check on their status, as well as to use it as a knowledge database for future re-occurences

Preserves the technical teams’ needs to track significant work in their own projects

Requires the least manual intervention to support it.

A Workflow Example#

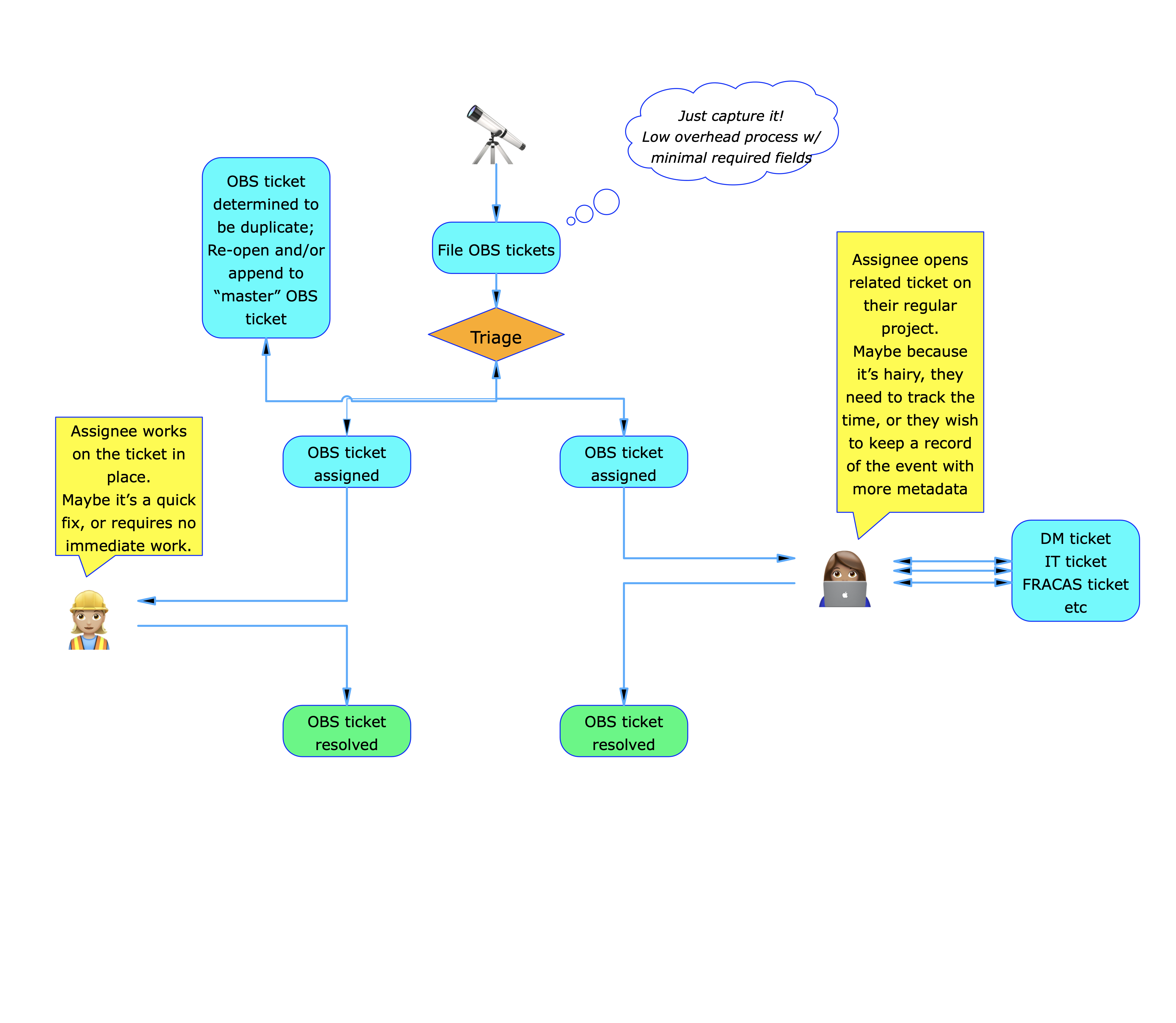

A simple representation of a worfklow based on OBS as the central entry point for night-time faults#

For the purposes of supporting discussion, here is a workflow that attempts to address the issues raised above:

Observers file tickets in the OBS project, which is lightweight on metadata (see Appendix A)

Technical staff either self assign if they see them first or…

… the operations manager ensures that tickets assigned to the appropriate team lead when they do their sweeps.

Technical staff decide whether to work on the ticket in situ, or whether they need to flush the work to a ticket in their own project, at which point they link the OBS ticket to the flushed out ticket. This enables multiple teams to flush out a compound problem (e.g., one OBS ticket might give rise to both a DM ticket and an IHS ticket, or both a mechanical maintenance ticket and a FRACAS ticket).

If the OBS ticket was not resolved in situ but was worked on a linked ticket, a helpful summary for status and further knowledge database searching is included in the OBS ticket before it is closed

Below are some common night time faults as illustrative examples.

The mostly-for-the-record ticket

Examples:

“The TV with the big LOVE display was blank when we arrived. We noticed the HDMI cable had fallen out - we replugged it in and duct-taped it in position”.

“An observer was briefly unwell. We stopped observing to evaluate them”.

These are tickets that log an incident but the observers took any necessary action. The observers close the ticket themselves, logging any time lost.

In some observatories these actions often are captured in a nightlog, or in the ticket system (here JIRA) or sometimes a mixture of both. Typically there is no further traffic on the ticket but they are still useful, e.g., in avoiding somebody reporting that a TV HDMI cable is suddenly wrapped in duct tape….

The information-eliciting ticket

“The data reduction issued a Warning about [X]”

“There’s a red light flashing in [Panel Y] “

“The fan in the main observer’s computer is making a strange noise”

These are tickets that can be closed after further information is provided e.g.,

“This warning was left after some troubleshooting and has already been removed from the version of the code that will be deployed in the next maintenance window.”

“This light always flashes when motion is detected in the dome. See [documentation]”

“We checked the motherboard and the computer is fine. You can ignore it.”

Typically the responder closes the ticket and the observer re-opens it if the information provided did not address their concern, e.g.,

“The computer might be fine, but the fan noise is driving us crazy. Please replace”

The quick-fix ticket

“The recently hired observer could not log onto the Science Platform.”

“The observer’s computer seems to be getting slower and slower.”

These are tickets that result in technical action, but the solution is quick and immediately applied, and the engineer determines it is not worth a further ticket, either because the issue was transient or because a technical ticket already exists, e.g.,

“The new staff member was not onboarded properly. We have added them and clarified the action needed in the documentation.”

“The computer’s network card was logging errors. We replaced it out of the spares. Please confirm it works fine for you now.”

Typically either the responder closes the ticket, or the responder asks for a fix verification after which the observer closes the ticket.

The Houston-we-have-a-problem ticket

“There are waffle patterns all over the data.”

“The camera warmed up.”

“My RSP notebook’s kernel occasionally dies unexpectedly.”

These are problems where there is no quick fix and significant time, effort, or both need to be applied in order to troubleshoot and resolve them. Typically after triage and troubleshooting a ticket (or even an epic) will result in a technical project e.g.,

In the OBS project:

“Significant engineering has to happen to address this issue (see linked DM epic). Meanwhile when this happens you can recover by doing [X].”

Meanwhile in the DM project:

“Following reports of notebook kernel abnormal terminations (see OBS-nnnn) we have determined our approach to memory management of our kubernetes cluster is flawed. This DM epic involves research on how best to optimize pod deployment to avoid overcommitting node memory and a refactor of the catalog service to avoid it driving the pods out of memory with particularly large result sets.”

When a solution is (eventually) in place a response is made and both the technical and OBS tickets are closed:

“This problem should no longer re-occur following the summit deployment of [X] version 4. See DM-nnnn for more details on how this was addressed.”

Note that what characterizes these tickets is that either because of time, effort or priority, the fix is a long time coming; they are not all necessarily catastrophic and/or urgent. A lot of software issues tend to fall in this category.

The long-lived problem re-occurence ticket

This is the second most frustrating type of problem for everyone concerned. It starts with something like

“The [X] dropped out and had to be reset.”

and the first response is like “huh weird, don’t see why, might be a one-off, closing” and then it happens again and again but not that often and there’s never any obvious reason, and sometimes letting the observer reset whatever it is is more pragmatic when there are Houston-we-have-a-problem things to be worked on.

These tickets present a problem in two ways:

How to detect and track re-occurences

How to determine when the re-occurences tip into “will you stop telling us to reset this and just fix it” territory.

One common way to do (1) is for the first OBS report of the error to become the umbrella ticket for the problem and additional re-occurrences are tracked there. If a new OBS ticket is filed (perhaps because the observer did not realise or remember that this is a long-running fault), it is closed with a reference to the umbrella ticket.

At Rubin there is a Systems Engineering team with an interest in monitoring long-lived systemic issue that may show that a system is not performing to its spec. So a solution would be for SysEng staff to open a FRACAS ticket once a problem is determined to be persistent, and use that as the umbrella ticket. In this case to avoid load onto observers, it would be technical staff that closed the OBS re-occurrence tickets and logged another incident to the umbrella ticket.

As for (2) this is one of situations where a designated person (such us an ops manager) periodically reviewing all tickets (or debriefing observers) may need to take action to draw management attention to the need for a permanent solution rather than a repeated application of workarounds.

The who-knows? ticket

This is by far the most frustrating observatory operations ticket for everyone concerned. It starts with a report of, say, a data artifact, and the telescope team goes “we looked and we can’t see anything” and the instrument team goes “everything seems fine here” and software goes “it’s probably in the hardware?” and so a ticket falls in limbo because it cannot be easily triaged to an appropriate team lead and meanwhile everybody is busy with things that are most definitely their problem.

This is again a situation where someone in an ops manager role needs to intervene and lead a cross sub-system effort to determine the sub-system(s) originating this fault, after which the ticket will morph into one of the previous types.

The up-side is the cross-system troubleshooting can be a fun cross-team activity 🙂 but this is a situation where the discussion needs to leave the ticketing system and take place face-to-face.

Appendix A: Jira workflows and fields (editorial)

This is another tension presented by the needs of the reporter, who really wants to type in their thing and run, and the needs of the assignee or manager, who wants as much classification as possible (which system, which component, software or hardware, bug or user error, etc).

Having done JIRA administration for decades now, the biggest mistake I see is people doing premature classification when setting up new projects. This can end up being hard to sustain, is a burden on the reporter who has to sit there and reflect on which fields to pick, and avoids the fact that there are many errors in an observatory that don’t fit neatly in any one category.

The most troublesome field of all though is “priority”. Everybody likes the idea of setting their ticket to high priority but this never really works - priority is not a value, it’s a rank on a fluid list: what was priority 1 becomes priority 2 the moment you set something else as priority one. There is an idea that there are “very important” and “less important things” but that is also not a plan that survives encounter with the enemy: sometimes a non-crticial thing that affects many people’s quality life should (and does) get done ahead of another item. My experience with people who insist on a priority field is that they start with 1, 2, 3 and then it goes to 1A, 1B, 1C and they they add critical and soon nothing means anything and everyone is demoralized at being asked why priority N is not getting done.

The important point is that you can never determine nuanced priority accurately at filing or even triage; it can only be determined in conjuction with an engineer’s load and development roadmap, which is why in agile it is best done when pulling tickets for assignment by technical managers and not before.

That said, there is one simple boolean flag that can be of great value to an observatory: the “Urgent” tickbox. This is a very simple value that is the equivalent to “if this doesn’t get fixed before next observing we are dead in the water and/or the data is useless”. In previous observatories I have worked in it was tantamout to an authorization of overtime -night, weekend, holiday, etc (even in best effort basis environments, you want to know whether that ticket that got filed on a Saturday night is worth booting up your laptop for). Abuse of this field is easily detected, and it clarifies rather the situation for engineers rather than overwhelm them.

Appendix B: Daytime work

Observers do rely on the ticketing system to understand what the status of issues they have opened, so the obvious question becomes “what about daytime work that might affect status that was not done as result of a ticket” - such as engineering work that should not have had an effect on observing but the fact that a system was worked on is useful information: if you know work on the A/C was done, and the A/C does not work, it is a hint that you should go check if someone forgot to turn the A/C back on after they were done.

This is a hard issue because it is closely related to preventative maintenance and good luck moving engineers away from whatever system they have for tracking that.

A much simpler situation is when something happened during the day but that is not a relevant fact. For example, if the RSP is down for a daytime visitor it is no different than it being down for an observer; if the TCS will not run up for daytime tests, it is no different than it not running up for data taking.

So a simple heuristic for this situation is: if this had happened at night would it be an OBS ticket? if the answer is yes, it is reasonable to keep it as an OBS ticket for daytime / bad weather situations too, to avoid the proliferation of systems and processes.